By Dr. Leah C. Windsor (The University of Memphis) and Dr. Robert Ostergard (University of Nevada, Reno)

How did media communicate the Ebola crisis of 2014, and how did the public respond? Analyses of media framing often focus on content and themes, but argue that syntax and sentiment also shape how audiences understand messages. We can learn about complex disasters and emergencies via many channels, including traditional news media, social media, speeches by political leaders, and post-hoc through official government correspondence. What this implies is that, while the information within messages is important, so too is the choice of language and how the message is said. The content (topics), sentiment, and syntax contribute to how an issue is framed to the general public through these sources.

Background to the Ebola crisis

Ebola Virus Disease (Ebola) is the kind of virus that writers and screenwriters have etched in the minds of people around the world (World Health Organization, 2014). From Richard Preston’s 1995 book The Hot Zone to and Wolfang Peterson’s film Outbreak, Ebola has become the quintessential viral nightmare, real or imagined. That popular perception has been the basis for attention-getting headlines when the African continent has faced outbreaks of the dreaded virus. While there are other similar viruses (such as Lassa Fever, Marburg hemorrhagic fever, and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever), Ebola is especially rare and deadly in people, with no known cure and vaccines still in trials.1

Ebola is a hemorrhagic fever that resides in animals in African forests. Humans are infected after coming into close contact with Ebola infected animals, known as a zoonotic spillover event (Richards, 2016). Currently, researchers speculate that fruit bats are the primary reservoir for the virus (Feldmann & Geisbert, 2011; Kinsman, 2012; Kuhn, 2008; Leroy et al., 2005). The virus infects humans when they come into close contact with infected animals, for example, with the consumption of bat meat, a primary bushmeat eaten by Africans (Zhang & Wang, 2014). Infected humans can then transmit Ebola to other people through direct contact with broken skin, mucous membranes, and bodily fluids, such as blood or secretions (World Health Organization, 2014). Ebola is a highly infectious virus; even the most limited exposure to an infected individual can result in the transmission of the disease. Transmission frequently occurs in hospitals or clinics where infected individuals are receiving treatment, in homes where infected individuals are being cared for by their loved ones, and during funeral rituals that expose participants to the virus (Richards, 2016).

In the deadliest outbreak of Ebola (2014-16), the initial case, or index patient, was reported in December 2013. An 18-month-old boy from a small village in Guinea is believed to have been infected by bats. Weak surveillance systems and poor public health infrastructure contributed to the difficulty surrounding the containment of this outbreak and it quickly spread to Guinea’s bordering countries, Liberia and Sierra Leone. By July 2014, the outbreak spread to the capitals of all three countries. This was the first time EVD extended out from more isolated, rural areas and into densely populated urban centers, providing an unprecedented opportunity for transmission. A total of 28,616 cases of EVD and 11,310 deaths were reported in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. There were an additional 36 cases and 15 deaths that occurred when the outbreak spread outside of these three countries.

What did US citizens care about?

Eighty-six percent of respondents knew that Ebola could be transmitted through blood and bodily fluids. However, a large percentage had some inaccurate knowledge and 19 % believed Ebola would spread to the U.S. Respondents favored mandatory quarantine (63 %) and travel bans (55 %). Confidence in the ability of the media and government to accurately report on or prevent a U.S. epidemic was low, but public attention was high.

Broadly defined, U.S. voters tend to disregard international issues in evaluating political candidates, with domestic issues being dominant in their calculus of political performance. U.S. voters, however, do blame and punish their elected leaders for events beyond their control, making international issues a neutral to negative proposition for leaders. If international issues proceed without incident, voters will perceive the issue as mundane or as routine. If the international issue goes awry, voters will punish the elected official whether they have any real control over the issue. This scenario becomes more complex if the international issue transcends the international-domestic boundary to become a direct national security concern as a threat to the government, people, or territory. This scenario unfolded in the Ebola crisis, as we will discuss.

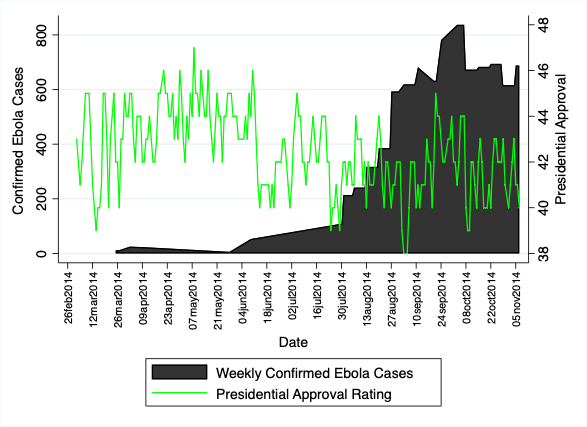

It would be difficult to assert that the Ebola crisis completely drove the president’s approval ratings during this period of time, given the contentious domestic agenda and the evolving crisis with Russia; however, it would be fair to say that the Ebola crisis was an amplifier to overall presidential approval ratings. Pew Research noted that interest in Ebola in this period was one of the top stories covered in the news since they began their tracking in 2010; it would be difficult to exclude Ebola as a factor in the president’s approval ratings. In fact, Ebola was a dominant topic in the midterm elections facing the president in the fall of 2014. Some of the lowest presidential approval ratings coincide with key events in the Ebola crisis.

Figure 1. Obama public approval and confirmed Ebola cases, 2014

While the crisis and its beginnings occurred in March 2019 at the same time problems in Crimea and Russia’s growing presence in that region had emerged, the real impact of the Ebola crisis on the president’s approval ratings can be seen in a few episodes of lower approval numbers later. As the number of Ebola cases increased over the middle to end of August 2014, his ratings bottom out at the end of August. At this point, the World Health Organization declared the Ebola outbreak the worst public health crisis in modern times and subsequently released its roadmap to combat the epidemic, which established a timeframe of 6-9 months to bring the outbreak under control. This announcement occurred at the same time as news broke that the epidemic was out of control and could spread to six other countries that were in danger of epidemic breakouts.

While the president’s approval climbed to the mid-40s as the number of weekly confirmed cases dipped in September, they sunk quickly as officials tally more cases through the rest of September. Despite a drop in confirmed cases toward the end of September, presidential approval dropped precipitously over this period as the president announced the US would take a lead role by sending 3000 US troops to the region along with millions of dollars in medical equipment and assistance. The key event that begins to highlight the critical nature of the outbreak for the United States occurs at the end of September when the epidemic comes home – US officials announce that an American citizen, Thomas Eric Duncan, had been admitted to a hospital in Dallas with a confirmed case of Ebola. The news reflected a growing sense with the American public that the epidemic was not contained and that the problem was no longer a distant, remote story.

Interestingly, Obama’s approval ratings rebounded by several points shortly after the death of Thomas Eric Duncan. We acknowledge that there are certainly other confounding factors that affect approval ratings. Yet given the salience of Duncan’s case and the Ebola threat more broadly, it seems in part that the rebound could be explained by his death and the public perception that the specific threat he posed, had been resolved. We rely on New York Times coverage of the Ebola topics to better understand the relationship among the crisis, the media, the leadership, and the public.

This blog comes in two halves. The second part of the research paper is published here.